Voyagers of Life

Cultural Anthropology has bent and twisted me in different directions of the world that surrounds me. It taught me to be curious, compassionate, resourceful, and open-minded. The same way that Ho’o’kua’aina, the organization of my choice for my ethnographic and service-learning project has touched my soul. While learning about the different societies and cultures with indigenous communities as a big theme in the class, I also had first-hand experience with the traditional practices of the Hawaiians through cultivating Kalo. Ho’okua’aina enlightened me with values I will try to sustain and live by.

The very core value of the organization, Nani ke kalo, taught me to do everything with a sense of purpose, love, care, and respect. The energy we put into our hands transfers over to the kalo that we, the people consume. This is why it is very important to treat the ‘aina, the kalo, and the people that surround us with respect. During my peaceful times submerged chest-deep into the lo’i and removing the weeds around the kalo, I remember thinking “I hope everyone can experience the serenity and the humility that I feel right now”. And with all the tension that has been building up, it led me to raise a question. Why should the people connected to the indigenous practices of a given land open the window of knowledge, opportunities, stories, art, and cultural traditions to all people?

The people connected to the indigenous practices of a given land should open their window of knowledge to all people because, at the very core, we are all living beings on this land trying to live. Acts of reciprocity between the land and the people and the people between other people will break the wall of tension, anger, selfishness, and fear that has built up over the years. Sharing knowledge and practices will sever the division amongst people. The more people that know about ecological knowledge, the more hands can help which will eventually aid in sustaining more resources for everyone. At the end of the day, we are all human. It is our kuleana, our responsibility to take care of our home. We are all in one big Va’a voyaging through life. Each one of us has an important role that keeps our vessel afloat. If we live and work with aloha, we are only strengthening our connection to the land and with each other.

Unfortunately, not everyone will think the same. We all come from different backgrounds and experiences which usually result in different opinions. Chris Hagar of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign does not agree to share indigenous knowledge globally “due to social capitalism and globalization”. Although I agree that indigenous people should not be treated as a form of intellectual property, I still believe that sharing will have a beautiful impact on the world. Hagar also shared Nicolas Gorjestani’s thoughts, a Program Director for the Indigenous Knowledge Program at the World Bank on having indigenous agencies at a local level. He believes that this will empower the indigenous communities to shape their development agenda by actively participating in the development dialogue, determining the research agenda, and exchanging knowledge of local practices that can help enable and empower local practitioners to improve the quality of life.

On the other hand, the United Nations, the keeper of peace, had some meetings about the protection and encouragement of indigenous identity, culture, and languages. Maria Fernanda Espinosa, the General Assembly President, believes that traditional knowledge mitigates climate change. That is why the UN, should “foster a better understanding of traditional knowledge and find ways to strengthen indigenous people’s voices.” Such as addressing the repayment of an enormous debt to the indigenous people. Anne Nuorgam, the Chair of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues expresses that it is “through our stories, songs, dances, paintings, and performances we transmit the knowledge between generations.” It is necessary to ensure that educational practices, languages, environmental conservation, and management are acknowledged and respected globally.

Before I started volunteering for Ho’okua’aina, I only saw them as no more than a kalo-producing farm. However, my view forever changed after my first day of volunteering for them. I had the opportunity to ask their Education and Outreach Coordinator, Makana Wilhelm a few questions. Within these exchanges of questions, this particular one stood out to me. “How does the organization’s mission help educate the public and cultivate the culture?” I had initially thought that that was the mission of Ho’okua’aina or at least I was trying to explain how Ho’okua’aina has affected me. But then she said, “I don't think our mission, our core, is really to educate everyone and to make sure that we're all on the same page. I'd say that it is just to open and create a gathering space where people can be intentional… we can pretend that we are growing the kalo, but really, it's the kalo that's growing us.” And in that moment, I realized that I had found my healing place. Even though I was chest-deep in the mud, pulling out weeds under the hot sun, and carrying heavy 55-gallon trash cans full of weeds, I felt cleansed and rejuvenated.

To wrap things up and reiterate my key points, Cultural Anthropology gave me the avenue to learn about the world around me. It also gave me the tools to conduct an ethnographic study that led me to connect with the ‘aina and with the people. So I say, yes, people with access to indigenous practices should open the knowledge window to share with all people.

However, there is a flaw to my argument. I am not considered an indigenous person. Although I had my hands muddy and helped take care of the kalo, I do not know what it feels like to be in their shoes. Nonetheless, with the little knowledge that I have gained and the values that I have cultivated, I was able to bring in like-minded people who share the same ethics as I do. They too will bring in people of their own and so on. Ho’okua’aina is the open window and the teacher is the ‘aina. Let us remember that each one of us has a purpose and a responsibility to take care of our resources because, at the end of the day, we are all living beings on a vessel voyaging through life.

Works Cited

“Indigenous People's Traditional Knowledge Must Be Preserved, Valued Globally, Speakers Stress as Permanent Forum Opens Annual Session | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases.” United Nations, United Nations, 22 Apr. 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/hr5431.doc.htm.

Hagar, C. “Sharing Indigenous Knowledge: To Share or Not to Share? That Is the Question”. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of CAIS / Actes Du congrès Annuel De l’ACSI, Oct. 2013, doi:10.29173/cais518.

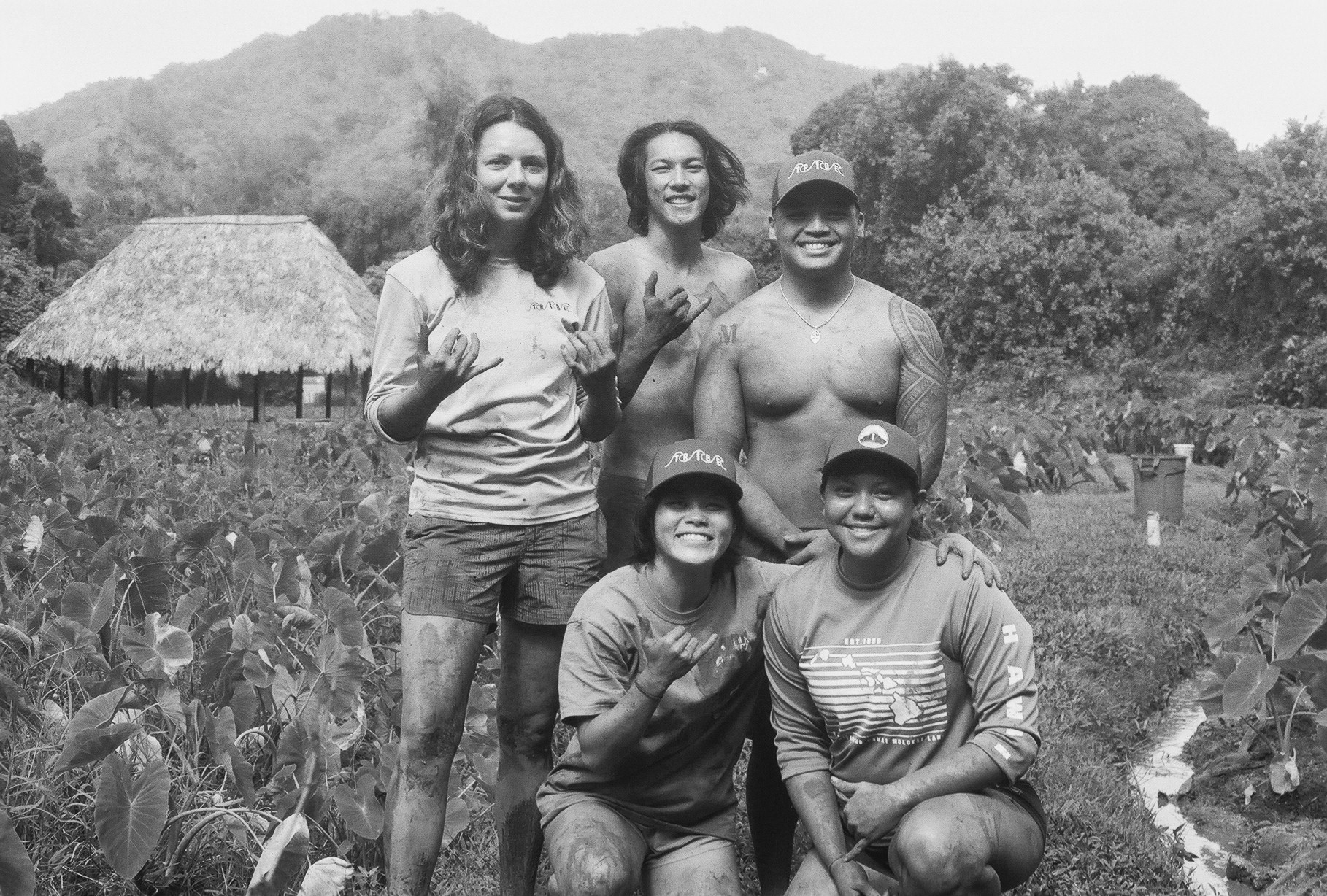

Hi! Thank you for taking the time to read and look through my service-learning project for my Cultural Anthropology class. This project meant a lot to me because I had the opportunity to offer my hands to Ho’okua’aina, an organization that opened my eyes and soul. I want to thank my Tribe Collective family for joining me on this journey and for being the subject of my lens. If you are interested in volunteering, here is the link to Ho’okua’aina: https://www.hookuaaina.org